Karma: this frequently heard word has entered most Western languages including English. The word karma comes from the Sanskrit root kri meaning “to do.” Karma translated is action, plain and simple, whether involuntary or voluntary, although as a religious term, karma often refers to intentional (usually moral) actions that affect our condition (or level of existence) in this life and the next.

We also hear of good karma and bad karma, which simply refers to actions that lead to positive or negative results. In Sanskrit, the word for result is “phala,” which means “fruit.” So the fruit of an action can be positive, negative or mixed. Hinduism adds an extra dimension to this understanding of karma, meaning the results of any given karma may not only bear “fruit” in this life, but may also bear fruit in a future lifetime. Similarly, actions performed in a former lifetime may be bearing results in this lifetime.

The concept of Karma (or kamma in Pali) is common to Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, but each interprets karma in different ways. According to Hinduism the concept of karma or “law of karma” covers the broad principle that all of life is governed by a system of cause and effect, of action and reaction, in which one’s deeds have corresponding effects on the future. Thus, karma is often used as a way of explaining evil and misfortune in the world, even for those who do not appear to deserve it; their misfortune must be due to wrong or “bad” actions in a previous life.

In Hindu texts, the word karma first appears in the ancient Rig Veda, but there it simply meant religious action and in both the Rig and the Yajur Vedas that sometimes involved animal sacrifice. There is some hint of the later meaning of karma in the Brahmanas, but it is not until the Upanishads that karma was expressed as a basic principle of cause and effect resulting from actions. One example is in Brhadaranyaka Upanishad 4.4.5. where it is said: “According as one acts, so does he become. One becomes virtuous by virtuous action, bad by bad action.”

So, Karma is commonly regarded today as a fundamental law of nature that is automatic and mechanical. It is not some personal vendetta that is imposed by God (or a god) as a system of reward and/or punishment, nor something that the gods can even interfere with.

In general usage today the word karma refers primarily to “bad karma”; that which is accumulated as a result of wrong actions (papa, or actions that split us from within and takes us away from integration). Bad karma binds a person’s soul (atman) to the cycle of rebirth (samsara) and leads to misfortune in this life and poor (or even miserable) conditions in the next incarnation. The moral energy of a particular act has a continuum which bears fruit (automatically) in the next life, and this may be manifested in one’s class, disposition, health, and character.

To offset “bad karma” Hindu texts prescribe a number of activities (e.g.; pilgrimages to holy places, acts of devotion, study of scriptures, etc.), that can wipe out the effects of bad karma. These positive actions (punya, or actions that bear positive results and elevate a person) may be referred to as “good karma,” and many believe the theory of karma embraces morally good acts as having positive consequences (not simply neutralizing wrong actions).

According to both Vedanta and Yoga teachings, there are three basic types of karma:

1. Prarabdha karma: Karma experienced during the present lifetime.

2. Sancita karma: The store of karma that has not yet reached fruition.

3. Agamin (or Sanciyama) karma and Kriyamana karma: Karma sown or accrued in the present life. Although in the same category, these two have subtle but significant differences.

· Kriyamana karma: Results of our current actions (instant karma).

· Agamin karma: Intended, or contemplated actions; precursors to future karmas.

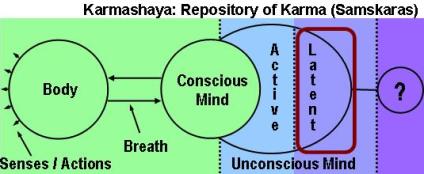

There is also the process by which karma is understood to work which involves various rebirths is as follows:

· Good or bad actions create impressions (samskaras) or tendencies (vasanas) in the mind, which in time will come to fruition in further action (more karma).

· The seeds of karma are carried in the subtle body (linga), in which the soul transmigrates.

· The physical body (sthula sarira) is the field in which the fruit of karma is experienced and more karma is created.

The purpose of life according Hindu scriptures is to minimize bad karma in order to enjoy better fortune in this life and insure a better (or higher) rebirth in the next. The ultimate spiritual goal is to achieve release (moksha) from the cycle of samsara (the endless cycle of birth, death and rebirth) altogether. Some believe this may take hundreds or even thousands of rebirths to rid oneself of all their accumulated karma and achieve moksha, while others believe it can be realized here, in this very life. But only until then can one be said to have found the true meaning of life. The person who has become liberated (attained moksha) creates no more new karma during the present lifetime and is not reborn after death.

Various methods to attain moksha are taught by different schools, but most include avoiding attachment to impermanent things, carrying out one’s duties without regard to results, and finally realizing the ultimate unity (yoga) between one’s soul or self (atman) and ultimate reality (Brahman).

Everyone’s karma is uniquely their own and is, in part, a result of previous incarnations, but we also share (collective) karmas, with our country of origin, our community, and our family and friends.

Karma entails the understanding that we are all ultimately responsible for our own lives. The self-determination and accountability of each individual soul rests on its capacity for free choice. This can only be exercised only in the human form. Lower species are devoid of the capacity to make moral decisions and are instead bound by instinct. Therefore, although all species of life are subject to the results of past activities, any such karma can only be generated while in the human form.

*Rae Indigo is ERYT500.

The ways we tend to act in our relationships and in the world are largely determined by impressions and our past is preserved, to the minutest detail, in the chitta (mind stuff), not the slightest bit is ever lost. The revival of samskaras induces smriti (memory). Memory cannot exist without samskaras.

The ways we tend to act in our relationships and in the world are largely determined by impressions and our past is preserved, to the minutest detail, in the chitta (mind stuff), not the slightest bit is ever lost. The revival of samskaras induces smriti (memory). Memory cannot exist without samskaras.